I sent this text to Anouchka three years ago upon her moving to China, and it came to me again recently, thought to pass it to you both now, upon commencement of our project for China… It is titled “Project for a trip to China”, a short story written in 1978 by Susan Sontag, one of eight stories collected in the book I, Etcetera (2002). hope you enjoy as much as I have…

.I

I am going to China.

I will walk across the Luhu Bridge spanning the Sham Chun River between Hong Kong and China.

After having been in china for a while, I will walk across the Luhu Bridge spanning the Sham Chun River between China and Hong Kong.

Five variables:

Luhu Bridge

Sham Chun River

Hong Kong

China

peaked cloth caps

Consider other possible permutations.

I have never been to China.

I have always wanted to go to China. Always.

.II

Will this trip appease a longing?

Q. [stalling for time] The longing to go to China, you mean?

A. Any longing.

Yes.

Archaeology of longings.

But it’s my whole life!

Don’t panic. “Confession is nothing, knowledge is everything.” That’s a quote but I’m not going to tell who said it.

Hints:

-a writer

-somebody wise

-an Austrian (i.e., a Viennese Jew)

a refugee

he died in America in 1951

Confession is me, knowledge is everybody.

Archaeology of conceptions.

Am I permitted a pun?

.III

The conception of this trip is very old.

First conceived when? As far back as I can remember.

–Investigate possibility that I was conceived in China though born in New York and brought up elsewhere (America).

–write M.

–telephone?

Prenatal relation to China: certain foods, perhaps. But I don’t remember M. saying she actually liked Chinese food.

–Didn’t she say that at the general’s banquet she spit the whole of the hundred-year-old egg into her napkin?

Something filtering through the bloody membranes, anyway.

Myrna Loy China, Turandot China. Beautiful, millionaire Soong sisters from Wellesley and Wesleyan & their husbands. A landscape of jade, teak, bamboo, fried dog.

Missionaries, foreign military advisers. Fur traders in the Gobi Desert, among them my young father.

Chinese forms placed about the first living room I remember (we moved away when I was six): plump ivory and rose-quartz elephants on parade, narrow rice-paper scrolls of black calligraphy in gilded wood frames, Buddha the Glutton immobilized under an ample lampshade of taut pink silk. Compassionate Buddha, slim, in white porcelain.

–Historians of Chinese art distinguish between porcelain and proto-porcelain.

Colonialists collect.

Trophies brought back, left behind in homage to the other living room, in the real Chinese house, the one I never saw. Unrepresentative, opaque objects. In dubious taste (but I only know that now). Confusing solicitations. The birthday gift of a bracelet made of five small tubular lengths of green jade, each tiny end capped in gold, which I never wore.

–Colors of jade:

green, all sorts, notably emerald green and bluish green

white

gray

yellow

brownish

reddish

other colors

One certainty: China inspired the first lie I remember telling. Entering the first grade, I told my classmates that I was born in China, I think they were impressed.

I know that I wasn’t born in China.

The four causes of my wanting to go to China:

material

formal

efficient

final

The oldest country in the world: it requires years of arduous study to learn its language. The country of science fiction, where everyone speaks with the same voice. Maotsetungized.

Whose voice is the voice of the person who wants to go to China? A child’s voice. Less than six years old.

Is going to China like going to the moon? I’ll tell you when I get back.

Is going to China like being born again?

Forget that I was conceived in China.

.IV

Not only my father and mother but Richard and Pat Nixon have been to China before me. Not to mention Marco Polo, Matteo Ricci, the Lumiere brothers (or at least one of them), Teilhard de Chardin, Pearl Buck, Paul Claudel, and Norman Bethune. Henry Luce was born there. Everyone dreams of returning.

–Did M. move from California to Hawaii three years ago to be closer to China?

After she came back for good in 1939, M. used to say, “In China, children don’t talk.” But her telling me that, in China, burping at the table is a polite way of showing appreciation for the meal didn’t mean I could burp.

Outside the house, it seemed plausible that I’d made China up. I knew I was lying when I said at school that I was born there; but being only a small portion of a lie so much bigger and more inclusive, mine was quite forgivable. Told in the service of the bigger lie, my lie became a kind of truth. The important thing was to convince my classmates that China actually did exist.

Was the first time I told my lie after or before I announced in school that I was a half-orphan?

–That was true.

I have always thought: China is as far as anyone can go.

–Still true.

When I was ten, I dug a hole in the back yard. I stopped when it got to be six feet by six feet by six feet. “What are you trying to do?” said the maid. “Dig all the way to China?”

No. I just wanted a place to sit in. I laid eight-foot-long planks over the hole: the desert sun scorches. The house we lived in then was a four-room stucco bungalow on a dirt road at the edge of town. The ivory and quartz elephants had been auctioned.

–my refuge

–my cell

–my study

–my grave

Yes. I wanted to dig all the way to China. And come bursting out the other end, standing on my head or walking on my hands.

The landlord came by in his jeep one day and told M. the hole had to be filled in within twenty-four hours because it was dangerous. Anyone crossing the yard at night might fall in. I showed him how it was entirely covered by boards, solid boards, except for the small square entrance on the north side where, with difficulty, I myself could just fit through.

–Anyway, who was going to cross the yard at night? A coyote? A lost Indian? A tubercular or asthmatic neighbor? An angry landlord?

Inside the hole, I scraped out a niche in the east wall, where I set a candle. I sat on the floor. Dirt fell through the cracks between the planks into my mouth. It was too dark to read.

–About to jump down, I never worried that I might land on a snake or a Gila monster curled up on the floor of the hole.

I filled the hole. The maid helped me.

Three months later I dug it again. It was easier this time, because the earth was loose. Remembering Tom Sawyer with the fence that had to be whitewashed, I got three of the five Fuller kids across the road to help me. I promised them they could sit in the hole whenever I wasn’t using it.

Southwest. Southwest. My desert childhood, off-balance, dry, hot.

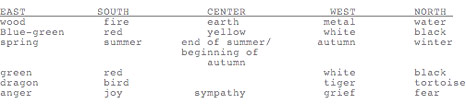

I have been thinking about the following Chinese equivalences:

I would like to be in the center.

The center is earth, yellow; it lasts from the end of summer through the beginning of autumn. It has no bird, no animal.

Sympathy.

.V

Invited by the Chinese government, I am going to China.

Why does everybody like China? Everybody.

Chinese things:

Chinese food

Chinese laundries

Chinese torture

China is certainly too big for a foreigner to understand. But so are most places.

For the moment I am not inquiring about “revolution” (Chinese revolution) but trying to grasp the meaning of patience.

And cruelty. And the endless presumption of the Occident. The bemedaled officers who led the Anglo-French occupation of Peking in 1860 probably sailed back to Europe with trunks of chinoiserie and respectful dreams of returning to China someday as civilians and connoisseurs.

–The Summer Palace, “the cathedral of Asia” (Victor Hugo), pillaged and burned

–Chinese Gordon

Chinese patience. Who assimilates whom?

My father was sixteen when he first went to China. M. was, I think, twenty-four.

I still weep in any movie with a scene in which a father returns home after a long desperate absence, at the moment when he hugs his child. Or children.

The first Chinese object I acquired on my own was in Hanoi in May 1968. A pair of green and white canvas sneakers with “Made in China” in ridged letters on the rubber soles.

Riding around Pnom Penh in a rickshaw in April 1968, I thought of the photograph I have of my father in a rickshaw in Tientsin taken in 1931. He looks pleased, boyish, shy, absent. He is gazing into the camera.

A trip into the history of my family. I’ve been told that the Chinese are pleased when they learn that a visitor from Europe or America has some link with a prewar China. Objection: My parents were on the wrong side. Amiable, sophisticated Chinese reply: But all foreigners who lived in China at that time were on the wrong side.

La Condition Humaine is called Man’s Fate in English. Not convincing.

I’ve always like hundred-year-old eggs. (They’re duck eggs, approximately two years old, the time it takes to become an exquisite green and translucent-black cheese.

–I’ve always wished they were a hundred years old. Imagine what they might have mutated into by then.)

In restaurants, in New York and San Francisco I often order a portion. The waiters inquire in their scanty English if I know what I’m ordering. I affirm that I do. The waiters go away. When the order comes, I tell my eating companions how delicious they are, but I always end up having all the slices to myself; everyone I know finds the sight of them disgusting.

Q. Didn’t David try the eggs? More than once?

A. Yes. To please me.

Pilgrimage.

I’m not returning to my birthplace, but to the place where I was conceived.

When I was four, my father’s partner, Mr. Chen, taught me how to eat with chopsticks. During his first and only trip to America. He said I looked Chinese.

Chinese food

Chinese torture

Chinese politeness

M. watched, approvingly. They all went back on the boat together.

China was objects. And absence. M. had a mustard-gold liquescent silk robe that belonged to a lady in waiting at the court of the Dowager Empress, she said.

And discipline. And taciturnity.

What was everybody doing in China all that time? My father and mother playing Great Gatsby and Daisy inside the British Concession, Mao Tse-Tung thousands of miles inland marching, marching, marching, marching, marching, marching. In the cities, millions of lean coolies smoking opium, pulling rickshaws, peeing on the sidewalks, letting themselves be pushed around by foreigners and pestered by flies.

Unlocatable “White Russians,” albinos nodding over samovars as I imagined them when I was five years old.

I imagined boxers raising their heavy leather gloves to deflect the hurtling lead of Krupp cannons. No wonder they were defeated.

I am looking in an encyclopedia at a photograph whose caption reads: “Souvenir photograph of a group of Westerners with the corpses of tortured Boxers. Honghong. 1899.” In the foreground, a row of decapitated Chinese bodies whose heads have tolled some distance away; it is not always clear which body each head belongs to. Seven white men standing behind them, posing for the camera. Two are wearing their safari hats; a third holds his at his right side. In the shallow-looking water behind them, several sampans. The beginning of a village on the left. Mountains in the background, lightly touched with snow.

–The men are smiling.

–Undoubtedly it is an eighth Westerner, their friend, who is taking the picture.

Shanghai smelling of incense and gunpowder and dung. A United States Senator (from Missouri) at the turn of the century: “With God’s help, we shall raise Shanghai up and up and up until it reaches the level of Kansas City.” Buffalo in the late 1930s, disemboweled by the bayonets of invading Japanese soldiers, groaning in the streets of Tientsin.

Outside the pestilential cities, here and there a sage crouches at the breast of a green mountain. A great deal of elegant geography separates each sage from his nearest counterpart. All sages are old but not all are hirsute enough to grow white beards.

Warlords, landlords; mandarins, concubines. Old China Hands. Flying Tigers.

Words that are pictures. Shadow theater. Storm Over Asia.

.VI

I am interested in wisdom. I am interested in walls. China famous for both.

>From the entry on China in the Encyclopaedia Universalis (vol. 4, Paris, 1968, p. 306): “Dans les conversations, on aime toujours les successions de courtes phrases don’t chacune est induite de la précédente, selon la méthode chinouse traditionelle de raisonnement.”

Life lived by quotations. In China, the art of quotation has reached its apogee. Guidance in all tasks.

There is a woman in China, twenty-nine years old, whose right foot is on her left leg. Her name is Tsui Wen Shi. The train accident that cost her her right leg and her left foot occurred in January 1972. The operation that grafted her right foot onto her left leg took place in Peking and was performed, according to the People’s Daily, “under the guidance of the proletarian line of Chairman Mao on matters of health, but also thanks to advanced surgical techniques.”

–The newspaper article explains why the surgeons didn’t graft her left foot back on her left leg: the bones of her left foot were smashed, the right foot was intact.

–The reader is not asked to take anything on faith. This is not a surgical miracle.

I am looking at the photograph of Tsui Wen Shi, sitting erect on a table covered with a white cloth, smiling, her hands clasping her bent left knee.

Her right foot is very large.

The flies are all gone, killed twenty years ago in the Great Fly-Killing Campaign. Intellectuals who, after criticizing themselves, were sent to the countryside to be reeducated by sharing the lot of peasants are returning to jobs in Shanghai and Peking and Canton.

Wisdom has gotten simpler, more practicable. More horizontal. The sages’ bones whiten in mountain caves and the cities are clean. People are eager to tell their truth, together.

Feet long since unbound, women hold meetings to “speak bitterness” about men. Children recite anti-imperialist fairy tales. Soldiers elect and dismiss their officers. Ethnic minorities have a limited permission to be folkloric. Chou En-lai remains lean and handsome as Tyrone Powers, but Mao Tse-tung now resembles the fat Buddha under the lampshade. Everyone is very calm.

.VII

Three things I’ve been promising myself for twenty years that I would do before I die:

–climb the Matterhorn

–learn to play the harpsichord

–study Chinese

Perhaps it’s not too late to climb the Matterhorn. (As Mao Tse-tung swam, didactically old, eleven miles down the Yangtze?) My fussed-over lungs are sturdier today than when I was in my teens.

Richard Mallory vanished forever, behind a huge cloud, just as he was sighted nearing the top of the peak. My father, tubercular, never came back from China.

I never doubted I would go to China someday. Even when it became hard to go, impossible even, for an American.

–Being so confident, I never considered making that one of my three projects.

David wears my father’s ring. The ring, a white silk scarf with my father’s initials embroidered in black silk thread, and a pigskin wallet with his name stamped in small gold letters on the inside are all I possess that belonged to him. I don’t know what his handwriting was like, not even his signature. The flat signet of the ring bears his initials, too.

–Surprising that it should just fit David’s finger.

Eight variables:

rickshaw

my son

my father

my father’s ring

death

China

optimism

blue cloth jackets

The number of permutations here are impressive: epic, pathetic. Tonic.

I have some photos too, all taken before I was born. In rickshaws, on camels and boat decks, before the wall of the Forbidden City. Alone. With his mistress. With M. With his two partners, Mr. Chen and the White Russian.

It is oppressive to have an invisible father.

Q. Doesn’t David also have an invisible father?

A. Yes, but David’s father is not a dead boy.

My father keeps getting younger. (I don’t know where he’s buried. M. says she’s forgotten.)

An unfinished pain that might, just might, get lost in the endless Chinese smile.

.VIII

The most exotic place of all.

China is not a place that I—at least—can go to, just because I decide to go.

My parents decided against bringing me to China. I had to wait for the government to invite me.

–Another government.

For meanwhile, while I was waiting, upon their China, the China of pigtails and Chiang Kai-shek and more people than can be counted, had been grafted the China of optimism, the bright future, more people than can be counted, blue cloth jackets and peaked caps.

Conception, pre-conception.

What conception of this trip can I have in advance?

A trip in search of political understanding?

–”Notes toward a Definition of Cultural Revolution”?

Yes. But grounded in guesswork, vivified by misconceptions. Since I don’t understand the language. Already six years older than my father when he died, I haven’t climbed the Matterhorn or learned to play the harpsichord or studied Chinese.

A trip that might ease a private grief?

If so, the grief will be eased in a willful way: because I want to stop grieving. Death is unremittable, unnegotiable. Not unassimilable. But who assimilates whom? “All men must die, but death can vary in its significance. The ancient Chinese writer Szuma Chien said, “Though death befalls all men alike, it may be heavier than Mount Tai or lighter than a feather.’”

–This is not the whole of the brief quote given in Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, but it’s all I need now.

–Note that even in this abridged quote from Mao Tse-tung there is a quote within a quote.

–The omitted final sentence of the quote makes clear that the heavy death is desirable, not the light one.

He died so far away. By visiting my father’s death, I make him heavier. I will bury him myself.

I will visit a place entirely other than myself. Whether it is the future or the past need not be decided in advance.

What makes the Chinese different is that they live both in the past and in the future.

Hypothesis. Individuals who seem truly remarkable give the impression of belonging to another epoch. (Either some epoch in the past or, simply, the future.) No one extraordinary appears to be entirely contemporary. People who are contemporary don’t appear at all: they are invisible.

Moralism is the legacy of the past, moralism rules the domain of the future. We hesitate. Wary, ironic, disillusioned. What a difficult bridge this present has become! How many, many trips we have to undertake so as not to be empty and invisible.

.IX

From The Great Gatsby, p. 2: “When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart.”

–Another “East,” but no matter. The quote fits.

–Fitzgerald meant New York, not China.

–(Much to be said about the “discovery of the modern function of the quotation,” attributed by Hannah Arendt to Walter Benjamin in her essay “Walter Benjamin.”

–Facts:

a writer

someone brilliant

a German [i.e., a Berlin Jew]

a refugee

he died at the French-Spanish border in 1940

–To Benjamin, add Mao Tse-tung and Godard.)

“When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world…” Why shouldn’t the world stand at moral attention? Poor, bruised world.

First half of second quotation from unnamed Austrian-Jewish refugee sage who died in America: “Man as such is the problem of our time; the problems of individuals are fading away and are even forbidden, morally forbidden.”

It’s not that I’m afraid of getting simple, by going to China. The truth is simple.

I will be taken to see factories, schools, collective farms, hospitals, museums, dams. There will be banquets and ballets. I will never be alone. I will smile often (though I don’t understand Chinese).

Second half of unidentified quote: “The personal problem of the individual has become a subject of laughter for the Gods, and they are right in their lack of pity.”

“Fight individualism,” says Chairman Mao. Master moralist.

Once China meant ultimate refinements: in pottery, cruelty, astrology, manners, food, eroticism, landscape painting, the relation of thought to written sign. Now China means ultimate simplifying.

What doesn’t put me off, imagining it on the eve of my departure for China, is all that talk about goodness. I don’t share the anxiety I detect in everyone I know about being too good.

–As if goodness brings with it a loss of energy, individuality;

–in men, a loss of virility.

“Nice guys finish last.” American saying.

“It’s not hard for one to do a bit of good. What is hard is to do good all one’s life and never do anything bad…” (Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, Bantam paperback edition, p. 141.)

A teeming world of oppressed coolies and concubines. Of cruel landlords. Of arrogant mandarins, arms crossed, long fingernails sheathed inside the wide sleeves of their robes. All mutating, peaceably, into Heavenly Girl & Boy Scouts as the Red Star mounts over China.

Why not want to be good?

But to be good one must be simpler. Simpler, as in a return to origins. Simpler, as in a great forgetting.

.X

Once, leaving China to return to the United States to visit their child (or children), my father and M. took the train. On the Trans-Siberian Railroad, ten days without a dining car, they cooked in their compartment on a Sterno stove. Since just one breathful of cigarette smoke was enough to send my father into an asthmatic attack, M., who smokes, probably spent a lot of time in the corridor.

–I am imagining this. M. never told me this, as she did tell me the following anecdote.

After crossing Stalin’s Russia, M. wanted to get out when the train stopped in Bialystok, where her mother, who had died in Los Angeles when M. was fourteen, had been born; but in the 1930s the doors of the coaches reserved for foreigners were sealed.

–The train stayed for several hours in the station.

–Old women rapped on the icy windowpane, hoping to sell them tepid kvass and oranges.

–M. wept.

–She wanted to feel the ground of her mother’s faraway birthplace under her feet. Just once.

–She wasn’t allowed to. (She would be arrested, she was warned, if she asked once more to step off the train for a minute.)

–She wept.

–She didn’t tell me that she wept, but I know she did. I see her.

Sympathy. Legacy of loss. Women gather to speak bitterness. I have been bitter.

Why not want to be good? A change of heart. (The heart, the most exotic place of all.)

If I pardon M., I free myself. She has still not, after all these years, forgiven her mother for dying. I shall forgive my father. For dying.

–Shall David forgive his? (Not for dying.) For him to decide.

“The problems of individuals are fading away…”

.XI

Somewhere, some place inside myself, I am detached. I have always been detached (in part). Always.

–Oriental detachment?

–pride?

–fear of pain?

With respect to pain, I have been ingenious.

After M. returned to the United States from China in early 1939, it took several months for her to tell me my father wasn’t coming back. I was nearly through the first grade, where my classmates believed I had been born in China. I knew, when she asked me to come into the living room, that it was a solemn occasion.

–Wherever I turned, squirming on the brocaded sofa, there were Buddhas to distract me.

–She was brief.

–I didn’t cry long. I was already imagining how I would announce this new fact to my friends.

–I was sent out to play.

–I didn’t really believe my father was dead.

Dearest M. I cannot telephone. I am six years old. My grief falls like snowflakes on the warm soil of your indifference. You are inhaling your own pain.

Grief ripened. My lungs wavered. My will go stronger. We went to the desert.

>From Le Potomak by Cocteau (1919 edition, p. 66): “Il était, dans la ville de Tien-Sin, un papillon.”

Somehow, my father had gotten left behind in Tientsin. It became even more important to have been conceived in China.

It seems even more important to go there now. History now compounds my personal, individual reasons. Bleaches them, displaces them, annihilates them. Thanks to the labors of the greatest world-historical figure since Napoleon.

Don’t languish. Pain is not inevitable. Apply the gay science of Mao: “Be united, alert, earnest, and lively” (same edition, p. 81).

What does it mean, “be alert”? Each person alertly within himself, avoiding the collective drone?

–All very well, except for the risk of accumulating too many truths.

–Think of the damage to “be united.”

Degree of alertness equals the degree to which one is not lazy, avoids habits. Be vigilant.

The truth is simple, very simple. Centered. But people crave other nourishment besides the truth. Its privileged distortions, in philosophy and literature. For example.

I honor my cravings, and I lose patience with them.

“Literature is only impatience on the part of knowledge.” (Third and last quote from unnamed Austrian-Jewish sage who died, a refugee, in America.)

Already in possession of my visa, I am impatient to leave for China. To know, Will I be stopped by a conflict with literature?

A nonexistent conflict, according to Mao Tse-tung in his Yenan lectures and elsewhere, if literature serves the people.

But we are ruled by words. (Literature tells us what is happening to words.) More to the point, we are ruled by quotations. Not only in China, but everywhere else as well. So much for the transmissibility of the past! Disunite sentences, fracture memories.

–When my memories become slogans, I no longer need them. No longer believe them.

–Another lie?

–An inadvertent truth?

Death doesn’t die. And the problems of literature are not fading away…

.XII

After walking across the Luhu Bridge spanning the Sham Chun River between Hong Kong and China, I will board a train for Canton.

>From then on, I am in the hands of a committee. My hosts. My gracious bureaucratic Virgil. They control my itinerary. They know what they want me to see, what they deem proper for me to see; and I shall not argue with them. But when invited to make additional suggestions, what I shall tell them is: the farther north the better. I shall come closer.

I hate the cold. My desert childhood left me an intractable lover of heat, of tropics and deserts; but for this trip I’m willing to support as much cold as is necessary.

–China has cold deserts, like the Gobi Desert.

Mythical voyage.

Before injustice and responsibility became too clear, and strident, mythical voyages were to places outside of history. Hell, for instance. The land of the dead.

Now such voyages are entirely circumscribed by history. Mythical voyages to places consecrated by the history or real peoples, and by one’s own personal history.

The result is, inevitably, literature. More than it is knowledge.

Travel as accumulation. The colonialism of the soul, any soul, however well intentioned.

–However chaste, however bent on being good.

At the border between literature and knowledge, the soul’s orchestra breaks into a loud fugue. The traveler falters, trembles. Stutters.

Don’t panic. But to continue the trip, neither colonialist nor native, requires ingenuity. Travel as decipherment. Travel as disburdenment. I am taking one small suitcase, and neither typewriter nor camera nor tape recorder. Hoping to resist the temptation to bring back any Chinese objects, however shapely, or any souvenirs, however evocative. When I already have so many in my head.

How impatient I am to leave for China! Yet even before leaving, part of me has already made the long trip that brings me to its border, traveled about the country, and come out again.

After walking across the Luhu Bridge spanning the Sham Chun River between China and Hong Kong, I will board a plane for Honolulu.

–Where I have never been, either.

–A stop of a few days. After three years I am exhausted by the nonexistent literature of unwritten letters and unmade telephone calls that passes between me and M.

After which I take another plane. To where I can be alone: at least, sheltered from the collective drone. And even from the tears of things, as bestowed—be it with relief or indifference—by the interminably self-pitying individual heart.

.XIII

I shall cross the Sham Chun bridge both ways.

And after that? No one is surprised. Then comes literature.

–The impatience of knowing

–Self-mastery

–Impatience in self-mastery

I would gladly consent to being silent. But then, alas, I’m unlikely to know anything. To renounce literature, I would have to be really sure that I could know. A certainty that would crassly prove my ignorance.

Literature, then. Literature before and after, if need be. Which does not release me from the demands of tact and humility required for this overdetermined trip. I am afraid of betraying so many contradictory claims.

The only solution: both to know and not to know. Literature and not literature, using the same verbal gestures.

Among the so-called romantics of the last century, a trip almost always resulted in the production of a book. One traveled to Rome, Athens, Jerusalem—and beyond—in order to write about it.

Perhaps I will write the book about my trip to China before I go.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] things in process…we are overseas […]

gold jewelry for women

I found a great…

Edmund Maves

I found a great…

Jacquiline Deitrick

I found a great…

Tanya Schettig

I found a great…

Willia Leapheart

I found a great…

Elijah Tetreault

I found a great…

Burma Resner

I found a great…

Nathan Simers

I found a great…

Sara Estock

I found a great…

Stevie Annunziata

I found a great…

Antone Firlit

I found a great…

craigslist free stuff ct nw

I found a great…

buy fast private proxies

I found a great…

where to buy proxies

I found a great…

elite proxy

I found a great…

seo proxies

I found a great…

gsa ser proxy

I found a great…

buy proxy server

I found a great…

proxies cheap

I found a great…

cheap proxy

I found a great…

senuke proxies

I found a great…

usa proxy

I found a great…

shared proxies

I found a great…

ghhome health agency in williamsburg va

“[…]things in process…we are overseas[…]”

ایران چارتر, ایران آنلاین تراول, سفر, هتل های ارزان, هتل , آژانس مسافرتی, رزرو هتل,

“[…]things in process…we are overseas[…]”

what is seo marketing

I found a great…

the camera shop muskegon

I found a great…

کورین ال جی

[…]things in process…we are overseas[…]

cash for cars

I found a great…

Easy Forex System

[…]things in process…we are overseas[…]

look younger with gray hair

I found a great…

corporate Proxy solicitation traduzione

things in process…we are overseas