Over-determining the function of an art practice can limit its power to transform, illuminate or respond to a given situation

第二次排练进程展示,2009年9月22日 | from the 2nd open rehearsal, 22 September 2009

第二次排练进程展示,2009年9月22日 | from the 2nd open rehearsal, 22 September 2009

Bourriaud argues that art of the 1990s takes as its theoretical horizon “the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space” (RA, p. 14). In other words, relational art works seek to establish intersubjective encounters (be these literal or potential) in which meaning is elaborated collectively (RA, p. 18) rather than in the privatized space of individual consumption. The implication is that this work inverses the goals of Greenbergian modernism. Rather than a discrete, portable, autonomous work of art that transcends its context, relational art is entirely beholden to the contingencies of its environment and audience. Moreover, this audience is envisaged as a community: rather than a one-to-one relationship between work of art and viewer, relational art sets up situations in which viewers are not just addressed as a collective, social entity, but are actually given the wherewithal to create a community, however temporary or utopian this may be.

[from Claire Bishop’s “Antagonism & Relational Aesthetics”]

Posted by e | reply »we think i forget

We Think

Each Thinks.

Some resonates.

This video thinks : “you are what you share”. Your riches is what you share, the more you share, the richer.

I disagree, I think :

“You are what you share” ?

You are what remains after you shared.

Sharing does not erase the self to be absorbed in the community.

The social value of a person may be what one shares, but the intrinsic value of one is what remains.

This is maybe a powerful modern times statement and the consequence is that the separation between the social self (what you share) and the intrinsic self (what remains) is only going to increase.

One cannot entirely share. One cannot entirely hold. How much of yourself do you share? What is the right balance?

In a time of almost forced collaboration, what remains is more and more precious. I’d rather use my avatar -instead of myself- to be participating this social flow, and not think – forget sometimes.

While the web 2.0 was made of communities of very active users, it largely became many massive communities of passive followers (fake contributors), participation became for most a passive activity. It used to be “We think” a state of emulation excitement, turned into “We think, I listen”, now “We think, I forget”, tomorow “We forget, I forget”.

“We” isn’t really anymore something I relate to, or I am a part of. We is the politically correct policy of individual participation that people must think I am part of to be socially accepted.

“We think, I forget” is what happened to the electoral and political landscape in most western countries, people got bored and dont participate anymore, except people who are raging for more power or desperate people. The same is happening to the internet. Look what happened to TV. But internet is different. I like to think beyond “We forget, I forget” there is “We forget, I think”, a context in which the individual went through this process of getting socially (politically) bored, than abandonning the virtual social reality to desire again to engage with it.

I believe this desire will be motivated, not because we are forced into it, but because individuals will find their accomplishments (self-interest) in new modalities of participation (general interest), maybe new technologies, new social structures.

Internet is now almost everywhere, so the infrastructure is there. The gap is physical. We need better interfaces… And better reasons to use them…

http://cesarharada.com/pearls/we-think/

Posted by sim | reply »collective intimacy

above: Diller Scofidio + Renfro with Julia Wolfe, Traveling Music

above: Diller Scofidio + Renfro with Julia Wolfe, Traveling Music

evento 2009

October 9 – 18, 2009

The artistic and urban rendez-vous of Bordeaux

First edition: Collective Intimacy

Curated by Didier Fiúza Faustino

evento 2009 is a new biennial event that will take place throughout the urban public space of the city of Bordeaux (France). This year’s edition will present artistic, theoretical and performative interventions by over 50 participants, articulated by the notion of Collective Intimacy, the concept proposed by its curator, Didier Fiúza Faustino:

“Now is the hour for the expression of a collective intimacy such as only cities can really harbor. Cities belonging to everyone as well as to each individual. Cities where general and private interests are no longer at odds, so that a sensitive, common heritage may be constructed. Devices must be invented so as to allow installations, performances and events to spread throughout the city as stealth monuments: stealth for their nomadic, ephemeral and elusive character, monuments as objects of celebration. These new kinds of monuments invest spaces everywhere. They insinuate, infiltrate, and insert themselves in the city, altering the existing with the unexpected. Acting as unforeseen urban events, they modify ordinary trajectories and cause all kinds of deviations. They are a pretext for intimate interactions between inhabitants and their city.

In the same way that live arts must reclaim the center, the city must be given back to its inhabitants, in a genuine spirit of sharing. Let each individual claim their own share of city intimacy and choose to protect it or to expose it if they wish. Let us give everyone a choice to recreate the urban environment in accordance with their desire.”

Collective Intimacy

The concept of collective intimacy is an invitation to consider the city as a mental territory that draws together the sum of the lived experiences and trajectories that constitute our inner sense of the city. Prior to any strictly physical territorial reality, the city represents the emotional territory of each one — our collective intimacy.

black swan

The Black Swan Theory (in Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s version) concerns high-impact, hard-to-predict, and rare events beyond the realm of normal expectations. Unlike the philosophical “black swan problem“, the “Black Swan Theory” (capitalized) refers only to events of large magnitude and consequence and their dominant role in history. “Black Swan” events are considered extreme outliers. Note that in his writings Taleb never uses the phrase “Black Swan Theory”; instead, he refers to “Black Swan Events” (capitalized).

Background

The theory was described by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his 2007 book The Black Swan. Taleb regards almost all major scientific discoveries, historical events, and artistic accomplishments as “black swans”—undirected and unpredicted. He gives the rise of the Internet, the personal computer, World War I, and the September 11, 2001 attacks as examples of Black Swan events.[1][2]

The term Black Swan comes from the 17th century European assumption that ‘All swans are white‘. In that context, a black swan was a symbol for something that was impossible or could not exist. In the 18th Century, the discovery of black swans in Western Australia[3] metamorphosed the term to connote that a perceived impossibility may actually come to pass. Taleb notes that John Stuart Mill first used the Black Swan narrative to discuss falsification.

Coping with Black Swan events

The main idea in Taleb’s book is not to attempt to predict Black Swan events, but to build robustness to the negative ones, while being able to exploit positive ones. Taleb contends that banks and trading firms are very vulnerable to hazardous Black Swan events and are exposed to losses beyond that predicted by their defective models.

Taleb states that a Black Swan event depends on the observer—a Black Swan surprise for the turkey is not a Black Swan surprise for the butcher, hence his idea is to “avoid being the turkey” by finding out where one may be exposed to being a turkey and “turn the Black Swans white”.

Identifying a Black Swan event

Based on the author’s criteria:

- The event is a surprise.

- The event has a major impact.

- After the fact, the event is rationalized by hindsight, as if it had been expected.

Non-philosophical epistemological approach

Taleb’s black swan is different from the earlier (philosophical) versions of the problem as it concerns a phenomenon with specific empirical/statistical properties which he calls “the fourth quadrant”.[4] Before Taleb, those who dealt with the notion of the improbable, like Hume, Mill and Popper, focused on the problem of induction in logic, specifically that of drawing general conclusions from specific observations. Taleb’s Black Swan has a central and unique attribute: the high impact. His claim is that almost all consequential events in history come from the unexpected—while humans convince themselves that these events are explainable in hindsight (bias).

One problem, labeled the ludic fallacy by Taleb, is the belief that the unstructured randomness found in life resembles the structured randomness found in games. This stems from the assumption that the unexpected can be predicted by extrapolating from variations in statistics based on past observations, especially when these statistics are assumed to represent samples from a Bell Curve. These concerns are often highly relevant in financial markets, where major players use value at risk models (which imply normal distributions) but market return distributions have fat tails.

More generally, decision theory based on a fixed universe or model of possible outcomes ignores and minimizes the impact of events which are “outside model”. For instance, a simple model of daily stock market returns may include extreme moves such as Black Monday (1987) , but might not model the market breakdowns following the September 11 attacks. A fixed model considers the “known unknowns”, but ignores the “unknown unknowns“.

Taleb notes that other distributions are not usable with precision, but often more descriptive, such as the fractal, power law, or scalable distributions; awareness of these might help to temper expectations.[5] Beyond this, he emphasizes that many events are simply without precedent, undercutting the basis of this type of reasoning altogether. Taleb also argues for the use of counterfactual reasoning when considering risk.[6][7]

taken from the definition of black swan on www.wikipedia.org

Posted by sim | reply »《里九外七》| “Inside 9 Outside 7″

老北京有一种说法:内九外七皇城四,九门八点一口钟。

老北京有一种说法:内九外七皇城四,九门八点一口钟。

“内九外七”指的是内城、外城的城门。

“内九外七”指的是内城、外城的城门。

“内九”,指的是东边儿的东直门、朝阳门;西边儿的西直门和阜成门;北边儿的德胜门、安定门;南边儿的崇文门、正阳门(前门)和宣武门。

“外七”是指明世宗为加强城防,在嘉靖三十二年增修的外城城门。与最北边和内城的”前三门”平行的是东便门和西便门,东西两边儿分别是广渠门和广安门,南边则是左安门、右安门和直通正阳门的永定门。皇城四门:东有东安门(现东华门),南有天安门,西有西安门,北有地安门。

“外七”是指明世宗为加强城防,在嘉靖三十二年增修的外城城门。与最北边和内城的”前三门”平行的是东便门和西便门,东西两边儿分别是广渠门和广安门,南边则是左安门、右安门和直通正阳门的永定门。皇城四门:东有东安门(现东华门),南有天安门,西有西安门,北有地安门。

“里九外七”中的“里”与“close”取同义,为近邻的意思,而“外”则与“overseas”取同义,为海外的意思。除此之外,“七”和“九”也分别在中文寓意中,也具有更加特别的含义。

“里九外七”中的“里”与“close”取同义,为近邻的意思,而“外”则与“overseas”取同义,为海外的意思。除此之外,“七”和“九”也分别在中文寓意中,也具有更加特别的含义。

七——先秦时代的“魂魄聚散说”称:人之初生,以七日为腊,一腊而一魄成,故人生四十九日而七魄全;死以七日为忌,一忌而一魄散,故人死四十九日而七魄散,这段话是说,人生下来的时候,以七天为一个阶段,每七天,一个魂魄形成,七七四十九天后,魂魄完全形成,这个人开始了他的生命。而人死后,也是以七天为一个时间段,每七天消散一个魂魄,七七四十九天后,魂魄完全消散,这个人从这个世界上消失。(所以,中国人在某人去世后,家人要为他“做七”,意思就是就是祭送死者,让他安息。)所谓“七七四十九”为一个轮回正是取义于此。

七——先秦时代的“魂魄聚散说”称:人之初生,以七日为腊,一腊而一魄成,故人生四十九日而七魄全;死以七日为忌,一忌而一魄散,故人死四十九日而七魄散,这段话是说,人生下来的时候,以七天为一个阶段,每七天,一个魂魄形成,七七四十九天后,魂魄完全形成,这个人开始了他的生命。而人死后,也是以七天为一个时间段,每七天消散一个魂魄,七七四十九天后,魂魄完全消散,这个人从这个世界上消失。(所以,中国人在某人去世后,家人要为他“做七”,意思就是就是祭送死者,让他安息。)所谓“七七四十九”为一个轮回正是取义于此。

此外如天以阴阳二气及金、木、水、火、土五行演生万物,谓“七政”,人得阴阳、五常而有“七情”,故天之道惟七,人之气亦惟七;以及《易·系·复》曰“七日来复”,《礼记·檀弓上》日“水浆不入口者七日”。这些都是说“七”在中国人对人、天、地的认识中的重要性。

此外如天以阴阳二气及金、木、水、火、土五行演生万物,谓“七政”,人得阴阳、五常而有“七情”,故天之道惟七,人之气亦惟七;以及《易·系·复》曰“七日来复”,《礼记·檀弓上》日“水浆不入口者七日”。这些都是说“七”在中国人对人、天、地的认识中的重要性。

九——“九九归一”虽然指的是“周而复始”或“归根到底”,但不是原地轮回,而是由起点到终点、由终点再到新的起点,这样循环往复,以至无穷,螺旋式前进和发展的运动过程。它体现了人类对一切事物发展认识的辩证唯物论的哲学思想。 佛语有云:“九九归一、终成正果”。在这里,“九”是最大的,也是终极的,古今人文建筑都以之为“最”。要想“九九归一、终成正果”,还需要“一四七,三六九”,一步一步往前走。九九归一即从来处来,往去出去,又回到本初状态。其实,这种回复不是简单的返回,而是一种升华,一种再造,一种涅盘,更是一个新的起点。

九——“九九归一”虽然指的是“周而复始”或“归根到底”,但不是原地轮回,而是由起点到终点、由终点再到新的起点,这样循环往复,以至无穷,螺旋式前进和发展的运动过程。它体现了人类对一切事物发展认识的辩证唯物论的哲学思想。 佛语有云:“九九归一、终成正果”。在这里,“九”是最大的,也是终极的,古今人文建筑都以之为“最”。要想“九九归一、终成正果”,还需要“一四七,三六九”,一步一步往前走。九九归一即从来处来,往去出去,又回到本初状态。其实,这种回复不是简单的返回,而是一种升华,一种再造,一种涅盘,更是一个新的起点。

但愿里七外九(OVERSEAS, CLOSE BY)在带您经历惊喜之后,也能带给您人生一个新的起点。

但愿里七外九(OVERSEAS, CLOSE BY)在带您经历惊喜之后,也能带给您人生一个新的起点。

[text and research by 南景 Nan Jing]

Posted by admin | reply »Border Control, or, an ode to our groupings, where art (performance) and life (nature) are questioned…

Destroy art, eliminate artists; we know what dictators do when they assume power. All great art has the capacity to speak subversive truths, and can become a visible threat to a repressive regime. And yet how is it that during the devastating eight-year regime of George W. Bush – a man constantly at war with the truth – there was no meaningful campaign by his administration to bring down the arts? While it went to extreme lengths to silence critics, remove dissenting voices from positions of authority and rewrite the work of scientists to suit their agenda, artists were virtually ignored.1 It may be comic to imagine the government actually going after an artist, but tragic when you consider our irrelevance – we were not even perceived as a worthy threat to the Bush administration’s deceitful agenda. Or worse, has art become simply another tool of mass distraction at the service of the consumer-entertainment culture that blinds us to the truth of what is really happening in the world around us?

Posted by e | reply »Our community of art – and by extension, dance, poetry and theatre – has done an effective job of marginalizing itself into virtual irrelevancy for the general public. We are in a self-imposed exile and the Bushes and Cheneys of the world couldn’t have done a better job of it. We carry out our business safely out of view. We sequester ourselves in the quarantined cell of the studio, at exclusive gatherings in white cubes, and at clandestine performances in black boxes. We talk to ourselves in an endlessly self-referential hermetic discourse – like a snake eating its tail. When we’re on the radar of the mainstream, it tends to be empty entertainment or record-setting auction prices, a sensational but ultimately hollow spectacle. We patrol our own borders, making sure nothing unworthy is allowed to enter and that everything inside is too precious for the rest of the world to participate in. When we do invite participation, it’s on our own terms, and we’ve already decided what will happen anyway. I don’t want to sound hostile to the communities that I love, but I speak here using hyperbole, generalizations and partially unfair characterizations to make a point.

Politics is short and art is long. Things feel different now that Bush has gone and the global economy is recalibrating for a new age of austerity, although neither event seems to have had any impact on the way we are contributing to the gradual collapse of our natural environment. It’s not the job of art to solve problems, but the artist who responds to his or her time can help us feel the truth of the moment, which may be an end in itself, or the start of something else. I don’t pretend to have a revolutionary response to any of these issues, and have yet to figure out how to adequately address them in my own work. I do have a general feeling, though, that I want to see art that questions the systems and structures that we have inherited, in particular our sociological, geographic, and – especially – our disciplinary borders. These can be fortified divisions or porous membranes that give and take, responding to changing conditions. The borders between home and ‘not home’, city and ‘not city’, art and ‘not art’ have been particularly on my mind in my work lately.

We say we are home when we arrive back in our motherland, neighbourhood, car or favourite chain store. Our mobile phone numbers and email addresses follow us wherever we go. For many today, especially young people, I imagine that the homepage of their social networking site elicits stronger sensations of being at home than the physical structure that shares the name. Many of my projects take place in an actual private homes, or on the land around it – planting vegetable gardens in front lawns from London to Salina, or hosting a salon or a school at my geodesic dome residence in Los Angeles.

I recently made an open call to residents of Miami interested in starting a series of public gatherings in their homes. Keith Waddington and Mindy Nelson of Coral Gables responded, and the entire contents of their living space was reinstalled in the same arrangement in the galleries of the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami. For the newly public homes I designed an environment with floor cushions and pillows conducive to its role as a welcoming civic gathering space. Back at the museum, visitors could make themselves at home on the sofa in the transplanted living room and watch a video of Keith and Mindy hosting events for neighbours and members of their community, many of whom they were meeting for the first time.

To be territorial – to define the borders of our occupation – is not just a human trait, but is found everywhere in nature. Animals may not recognize our political borders, but they have their own. The few top males in a herd of Ugandan kob each preside over a 20-metre-wide grassy stamping ground where they mate. The male cicada-killer wasp will stake out a perch on his territory above the burrow of his subterranean colony and attack trespassing creatures. The male bowerbird will make a clearing, decorate it with colourful objects and use it as a performance stage, dancing to attract a female. Humans are one of many territorial creatures that occupy the planet, but we are the only ones who, when establishing territory, preclude the existence of most other life forms that we have not domesticated.

How does our perception of ‘not city’ change when we get five bars of mobile reception, smog alerts and a 747 flying above us? Is a city defined by the presence of people or by the absence of wildlife? I have become interested in loosening our tight-fisted grip on our urban centres, strategically welcoming the wild back. In 2008 in the Sculpture Court in front of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, I installed homes – entitled ‘Animal Estates’ – for 12 animals that lived at that precise location 400 years ago. They included a huge nest for a bald eagle, a wood wall with holes for solitary mason bees, and a nestbox for a barn owl on a 10-metre post at the corner of East 75th Street and Madison Avenue. Bronze plaques, printed materials and a series of weekly animal talks and performances accompanied the ‘Estates’, along with movements throughout the museum choreographed by 12 New York dancers – one for each animal. At the end of the exhibition most of the ‘Animal Estates’ were donated to Swindler Cove Park at the northern tip of Manhattan, where they have been permanently installed, encouraging those animals to once again take up residence on the island.

In her 1979 essay ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’ Rosalind Krauss analyzes the slippery, evolving nature of what was being referred to at the time as sculpture by artists including Carl Andre, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Robert Irwin, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra and Robert Smithson. Krauss talks about sculpture, and its relationship to ‘not architecture’ and ‘not landscape’. Recently the term ‘expanded field’ has been revived to help make sense of the work of a new generation of artists (including myself), whose legacy can ironically be traced directly back to artists from the 1970s whom Krauss does not mention in her essay. These include: Ant Farm, Buckminster Fuller, Anna Halprin, Joan Jonas, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Yayoi Kusama, Gordon Matta-Clark, Ana Mendieta, Adrian Piper and Yvonne Rainer, to name just a few personal favourites. They were working at the borders of what was known as sculpture, and some were outside what was even considered art. With our generation growing out of theirs, I would argue that the field has not expanded at all, but rather the ossified borders that previously separated it and other fields from each other are becoming more porous.

When I visit art students to discuss their work, I am often guided into a studio full of stuff. Sometimes, before they have a chance speak, I try to demarcate the border between art and ‘not art’ in the room. Once they have identified what we should be looking at and talking about, my eye is inevitably drawn to the ‘not art’ side of the room, which often seems more alive to me, more fun. Is it possible to make things, do things, before they are categorized? Is it possible to build a life’s work as a free-range human, freely meandering and trespassing without regard for the borders? Would it be helpful or liberating to live in a world where we could make what we want to see and do what we want to feel, only later deciding or understanding what it is, or how it should be classified? Ideas and impulses would be the motivation, and only later would the discipline be revealed.

‘Oh, I’ve been writing “poetry”, that’s what that is?’

‘Hey, I’ve been doing “theatre” all this time!’

‘Wow, I make “sculpture”?!’

‘So this is “dance”?’Children naturally operate this way, but it’s the opposite of how most formal education works. We are introduced to borders, decide which ones we want to surround ourselves with, learn what happened within them before we got there, and are then expected to perform within their narrow perimeters until we die. Though I found this sort of training helpful, some go deep but others go wide, and I soon began to wander. If I am interested in gardening, I don’t want to make work about gardens, I become a gardener, and go out into the city and make a garden. If I am interested in dance, I don’t want to make work about dancing, I enter into the dance community, and make dances in the streets. Animal homes, urban parades, domestic salons, compost piles, impossibly modest spaces – all are forums for life playing itself out. To be able to make the work that I am aiming to make – alive and engaged in a broader dialogue, straddling fields, disconnected conversations and discrete communities – I need to be prepared to make ‘not art’.

Why am I so ambivalent about identifying myself as an artist? Perhaps because it feels so presumptuous. Let others decide if what I am doing is indeed art. Even the act of writing the word ‘art’ is making me uncomfortable. It has such privileged and rarified connotations in our society, but at the same time everyone seems to be an artist. Maybe identifying myself as one limits my freedom by implying that everything I do aspires to be art. I’m not aiming for art, I’m aiming for life, and if art gets in the way, that’s fine. As the writer Annie Dillard finally realized when she was learning to chop wood, you have to aim for the chopping block not the wood.

When you enter United States, customs officials ask what you do. The last time I returned to the US from London, I made the mistake of hesitating.‘Well, um, yeah, ummmmm, let’s see … like uhhhhh.’

Getting confused answering simple questions raises red flags at border control.

I finally mumbled something about art.

‘Well, do you make art?’

‘Uh, I guess so, sort of, um, yeah.’

‘So you’re an artist?’

‘Um, OK, sure.’

‘Well what kind of artist are you?’I was tired and caught off-guard and not sure if this was an official line of questioning related to national security or if he was actually curious about my work. I flattered myself, thinking it must be a combination of both, but I couldn’t dismiss his question with a vague small-talk response as I normally would as this was an official enquiry from a federal agent. I became more flustered, and started rambling incoherently.

‘Um, well, I uh, make gardens sometimes. And, um, organize gatherings, parades sometimes? Dance and clothing … or like, uh, make homes for um, animals? And uh, books and videos? Sometimes teaching. And um, like also installations … .’

By now he seemed bored and confused.—- by fritz haeg, first published in frieze issue number 126 [and thank you to sportsbabel for the link. i am thinking…]

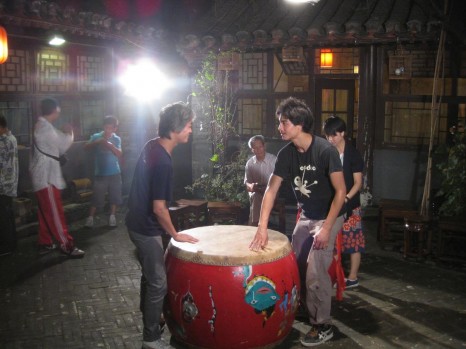

2009年9月22日 排练 | rehearsal 2009 september 22

照片 photos by 小梅 Xiao Mei and 三哥 Jam

Posted by e | reply »聋人工作坊–音乐、舞蹈、诗朗诵

9月4日,夜幕降临,灯光亮起,在何颖雅的饭饭工作坊结束之后,我们开始了由小河主持的音乐工作坊。看见了没有,那个大鼓。是前一天晚上从小河家拉过来的。他之前说家在天通苑,实际上是天通苑还得往北走好远,好远……

每个人都拿好自己的家伙什,严阵以待……

小河手中有节奏地挥舞着“鸡蛋”(类似于沙锤的打击乐器),示范给大家应该怎么做。在场的每个人人手一个……

舞舞舞……在场的每个人都玩high了,因为声响太大,又有人砸铁门抱怨了,不过,我们没有听见……

诗朗诵……

屋顶上,工作中的摄影师任杰……

屋檐下,同样在摄像的何颖雅,看见了么?人群的最右边……

会做饭吗?know how to cook?

交流、讨论,还有躲猫猫游戏

每天早上10点中开始,参加OVERSEAS项目的成员们都要热身、交流、讨论。每个成员都是切切实实参与到这个项目里来,和大家分享自己的一些想法及建议。

他们在看什么呢?

何颖雅最近一直忙着聋人工作坊的事情,现在又在忙着给晚上的活动所用灯光做准备。

小梅:我来摆一个!你来照一个!

躲猫猫游戏开始了,Simone(张秀芳)床底下找人。院子里、屋子里能多人的地方实在是太少了……

Monika(张秀娥)从冰箱后被逮了出来。

Simone怀疑大鼓下的木箱里会不会藏有人,最终在Jam的帮助下把大鼓搬开……没有人的,只有满满一箱子衣服。

萧薇在这个角落里已经窝了10多分钟了,出来的时候脖子都直不起来了。猫猫们(小珂、囡囡、Aloun)为了让老鼠们多受一些罪,跑出去买冰淇淋吃了。

小河躲在这个空调的后面,怕露出的脑袋太明显,放了一个塑料袋在空调上。猫们看到这个塑料袋反而知道他在后面了。唉!聪明反被聪明误哦!

大家看见了没有,小珂还在吃着呢!

小珂把自己放在一个瓦缸里,不管怎么努力,那个玻璃盖始终还是盖不上。

开工啦!开工啦!

开工就有开工饭,人马基本上都到齐了,偌大一个桌子,满了!

开始做事情前都要讨论讨论怎么干……

初步讨论完了,就该好好研究研究这个空间了。

瞧瞧这里,还有上房的……

都去忙了……

前面是分组讨论,在基本考查完整个院子的空间以后,偶们还要集体讨论。

没事了,来热热身吧!

我们在一起有什么意义?what does it mean for us to be together?

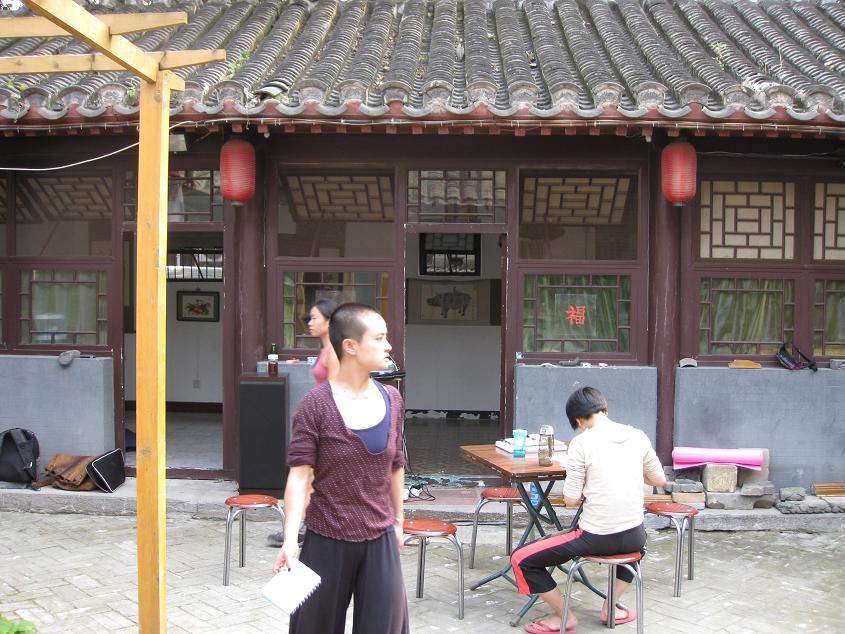

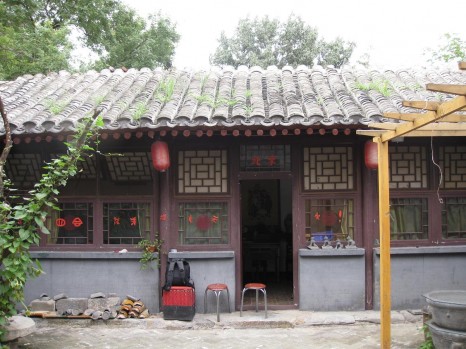

我们的那个四合院

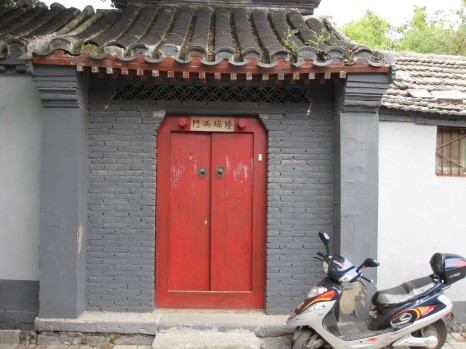

因为《Overseas》项目北京部分需要在一个四合院中进行,所以在历尽周折之后,八月份的时候,我们在靠近中南海的一个胡同找到了现在生活、排练的场所。

起初因为只有这扇侧门上有锁,所以进出院子的时候都是它了。毕竟年久失修,这扇铁门已经锈迹斑斑,严重变形,每次开关的时候都会发生巨大声响,以至于有时晚上晚一点点的时候,它的咳嗽声引来周围邻居的抱怨。还好,自从正门装上锁以后,它就可以休息了。

夏季,下一季呢?

minimal posting means we’ve been busy! the courtyard is full, our workshop has finished filming and a 非常大的感谢为所有参加的聋人朋友!吃的好饱,玩的很开心~

and here’s to 互助 huzhu in action…

庆祝overseas

小梅,非常感谢!!!

小梅,非常感谢!!!